546 Page and 59,329 Note Music Odyssey

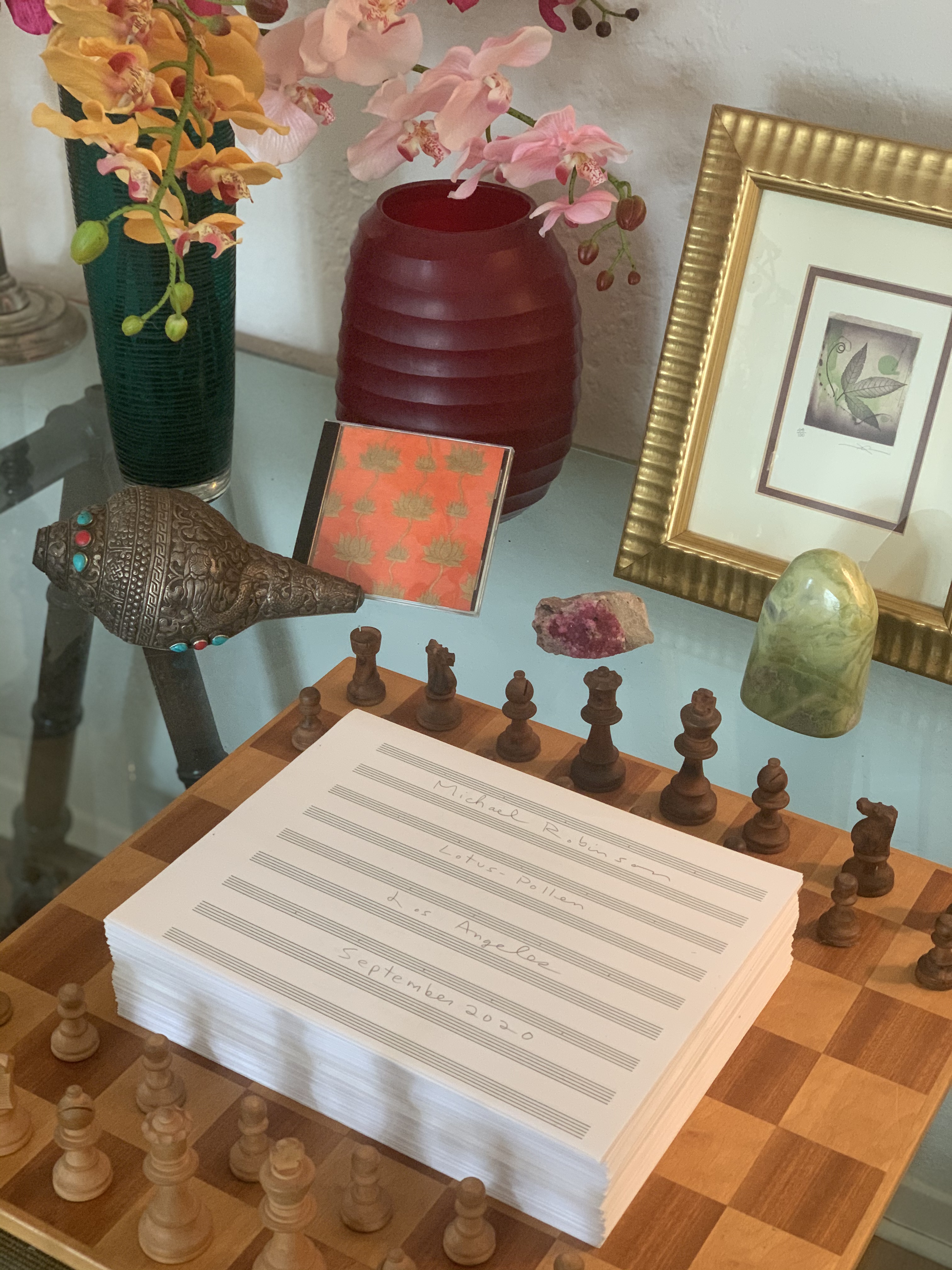

Lotus-Pollen by Michael Robinson original manuscript score together with the subsequent release.

A conch shell announces the concluding Drut Gat

Leonard Altman once related to me how some music looks better in the score than it sounds, referring to such as "eye music," using a Germanic phrase I don't recall at the moment. For myself, scores are tools used to create performances of my music. Asking to see one of my earlier autograph scores, Nelson Sullivan remarked upon how beautiful the notation was, and I do endeavor to make my manuscripts as legible and graceful as possible, but not to the point of interfering with the natural flow while composing. I have noticed that my musical handwriting has gradually become somewhat wilder over the years in terms of appearance, yet it remains entirely readable, a professional copyist recently complimenting me for such. It is only after I feel a composition is completed that I set about notating the details. For my most recent work, Lotus-Pollen, this happened to require 546 pages and 59,329 notes or swaras (tones) and bols (percussion tones), the Meruvina providing such details if prompted. As is my custom, not a single swara or bol was changed from the original notation because, again, I only commence notation after the music appears fully as a momentary flash within me after a period of musical contemplation.

The opening Alap (touch a color) of Lotus-Pollen has the fewest number of notations among the four movements.

The second movement Vilambit Gat (slow composition) of Lotus-Pollen has a considerable number of notations.

The third movement Madhya Gat (medium composition) of Lotus-Pollen also has a considerable number of notations.

The concluding Drut Gat (fast composition) of Lotus-Pollen has the highest number of notations among the four movements.

On one memorable occasion, I had opportunity to address a single question to bansri artist Hariprasad Chaurasia, querying him as to whether it was more difficult to play slow music or fast music. Hariprasad gave a wonderfully magnificent reply, with a deep sigh stating how both were monumentally difficult to execute properly, including mentioning breathing and delicacy for Alap (slow music), and technical mastery for Drut Gat (fast music) among other pertinent qualities demanded of both extremes. I will add that both apply equally for composition, this being a most physical as well as intellectual discipline. Additionally, while enjoying dinner with Hariprasad and Popatlal Savla, someone came to take the former's finished plate, but the legendary maestro would have none of that, instead rising to clear his own plate into the garbage, his touching humility not allowing any special treatment. Because I use my scores to create Meruvina performances, I have not had them printed using standard professional notation to date, but this is being looked into now for allowing others to have an alternative for studying or creating new performances from the original format. Heck, I want to see my scores in this format, too, just out of curiosity. A chess board and pieces was included in the photo of my Lotus-Pollen autograph score partly because chess and raga are unparalleled ingenuous inventions from India, both offering infinite intellectual and creative exploration; one based upon warfare in the form of a game, the other upon God and nature in the form of music. And as noted above, music composition, like chess, is simultaneously a corporeal and intellectual adventure. - Michael Robinson, January 2021, Los Angeles

© 2021 Michael Robinson All rights reserved

Michael Robinson is a Los Angeles-based composer, programmer, pianist and musicologist. His 199 albums include 152 albums for meruvina and 47 albums of piano improvisations. Robinson has been a lecturer at UCLA, Bard College and California State University Long Beach and Dominguez Hills.

|